Press

Quartet performs masterfully before sparse audience

by Richard Chon

Reprinted with permission from The Bakersfield Californian.

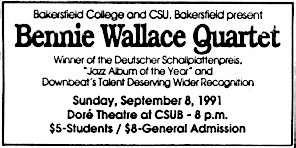

Sunday evening's concert by saxophonist Bennie Wallace at the Dore Theater was one for the cognoscenti.

You could tell by looking at the room: barely 50 people showed up to hear on of the most imposing jazz improvisers on this or any scene. If Sunday's paltry attendance was any indication of how seriously jazz is taken in Bakersfield, one would have to be seriously discouraged.

Compounding the frustration was the fact that Wallace and his quartet played what was probably the finest, most richly satisfying evening of jazz that this town's heard in two years.

Wallace is a phenomenal horn player, a tenor titan who is intimately acquainted with the mainstream tradition of his instrument and whose own playing is remarkable for a sensibility that combines historical reverence with a wholly fresh and spontaneous approach to style.

You could hear the history of the saxophone in every solo Wallace played. There was Ben Webster's suavity and strength (not to mention his breathy embouchure) that Wallace put to good use on ballads like "It's The Talk of the Town."

There was the stringent elegance of Charlie Parker in Wallace's refusal to indulge in obvious sentimental gestures. Wallace obviously shares Bird's aesthetics, the belief that true beauty is expressed in the pure objective lyricism of architectural grace, in a severity of line that knows no cliches.

Most obviously, there was Eric Dolphy's nervy tight-rope soul, an approach to improvisation that toed the tense line between tradition and experimentation. Like Dolphy, Wallace uses the riffs and melodic outlines of be-bop but injects a sophisticated harmonic consciousness that gives his solos an abstract, often anxious modern feel.

Like Dolphy, Wallace has an uncanny ability to pull ideas out to the most oblique, dissonant outland and relate them to the greater whole in the next few utterances. Which is the say, every note he played made an abstruse but inevitable sense. Wallace, in one blazing, inexhaustibly inventive solo after another, proved himself an expert navigator in that netherworld between "inside" and "outside."

He was aided by excellent sidemen, especially the brilliantly virtuosic drummer Alvin Queen, who is an acutely sensitive accompanist, not to mention a melodic soloist in the Max Roach tradition--the kind of guy in whose solos you can follow the shifts in tension between verse, bridge and back. There was a taste and logic here, but transcendent showmanship as well.

Guitarist Jerry Hahn was especially gratifying in his floating, Bill Evans-inspired chordal introductions to ballads. As a single-line soloist, he was perhaps too obsessed with exploring the harmonic ramifications of sequential riffs. If you heard an interesting idea from him, the chances were good you'd hear it again and again.

In Bill Huntington, Wallace had a bassist of firm comping convictions and gentle, ruminative solo ideas.

And in a guest appearance but California State University, Bakersfield jazz Professor Doug Davis on piano, Wallace had back momentarily a friend and colleague of 20 years, contributing some nice chordal backing and decorous improvisation on a brisk waltz version of "Stella By Starlight."

Those who heard them experienced a connoisseur's rich subtle pleasure. Those who didn't probably didn't care too much, and it's pretty difficult for us to care anything about you.